Everything✥Well, maybe not everything, but an awful lot of useful things for sure. you need to know about life, you can learn from Italian card games

In former times, when electronic entertainment was nonexistent, our forefathers devised a number of brilliant and ingenious ways to look busy, lest our foremothers find yet another task for them to do around the house. Among those that have transitioned well to electronic formats are card games, a pleasant way to make friends — as well as enemies, I reckon. I’ve been lucky enough to learn, play, and often forget War, Go Fish, Crazy Eights, Uno, Hearts, Poker, Pinochle, Дурака, Scopa, and Briscola. These days I generally play Scopa and Briscola online, so the reflections given below are based on my recent experiences with those games. This should go without saying, but since it doesn’t, I will: these observations are on the world as it is, not on the world as it should be.Scopa and Briscola

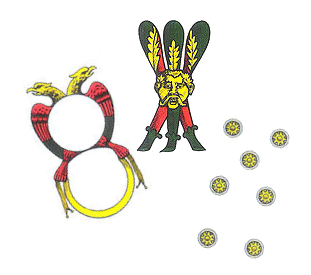

Some familiarity with the games will help; they aren’t too complex. In my experience, Scopa and Briscola are generally played with 40-card decks. Different regions of Italy have their own historical designs, and the three cards depicted below come from the Neapolitan design, the kind I grew up with.

(Yes, I did a bad job editing this image.)

Scopa

Translatable as “Broom” or “Sweep”, the game consists of taking cards from the table. You can match the value of a card on the table with one in your hand, or, if multiple cards on the table add up to the value of a card in your hand, you can take all the cards in the sum. Scoring is as follows:- one point for taking the most cards;

- carte da denaro: one point for taking the most golden cards;

- il settebello: one point for taking the golden seven;

- primiera: one point for a complicated point scoring system that I won’t waste time elaborating beyond saying that you if you collect at least three sevens, then you’ve probably won the point (but only probably);

- scopa: one point for each time you sweep the table of cards.

Briscola

Translatable, at least in this case, as “Trump”, the game is one of collecting cards of value. The trump suit is determined by dealing three cards to each player, then turning over the top card and placing it under the deck so that everyone can see it. Players do not have to follow suit, and can play a trump card whenever it suits their fancy. Cards have ranks and values:- l’asso: the one is an “ace”, worth eleven points;

- the three is worth ten points;

- the king, horseman, and jack are worth 4, 3, and 2 points each;

- all other cards are worth 0 points, but otherwise trump cards of their own suit according to their face value, with the exception that any card of the trump suit trumps any card of any other suit.

Good lessons

You’ll enjoy it more if you’re humble

Card games are fun. Sometimes you win, often you lose, but whether you have fun depends on your attitude. Or, as Thackeray wrote in Vanity Fair,

Life is a mirror:

if you frown at it, it frowns back; if you smile, it returns the greeting.

I’ve played thousands of games, mostly online,

and it always seemed that the angriest people who least enjoy the game

are the ones who take it “too” seriously.

They also tend to be the ones who lose more.

I’ll have more to say on this below, but which causes which?

Do people who enjoy the game enjoy it because they win more,

or because they don’t take it too seriously?

Or, do they win more because they don’t take it too seriously?

I suspect these go hand-in-hand:

a better attitude is less likely to cloud the mind,

which means you’re more likely to learn from your mistakes,

which means you’re more likely to win.

Likewise, losing a lot of games in a row can be frustrating,

which can cloud the mind, which can reinforce unhelpful behavior.

I’ll repeat this below, but it bears saying more than once:

You can’t choose the cards you’re dealt;

you can only choose how you play them.

Being sour about your lot,

especially when your cards really aren’t that bad,

won’t make other people more likely to play you,

especially when their cards really aren’t that good!

And that matters because…

Interacting with other people makes it more interesting

Most online games go by without a word being said, and a lot of players are explicit that they don’t want to chat. A few apps even allow you to turn off the chat entirely. Fine. I can play in silence just as badly as I do in full chat, though I’ll probably play worse in full chat, so if you’re playing me then it’s probably to your advantage to talk with me. That said, sometimes I’ll encounter someone who wants to chitchat. That’s almost always more interesting than the game. I get to learn about where they live (usually Italy, but it’s not all the same), what people do, what pets they have, why they’re playing (waiting for a bus? for a ride? avoiding work? to meet people?). It doesn’t sound so interesting when I write it, but maybe that’s because we don’t value ordinary people enough. Honestly, is that celebrity’t latest affair really that interesting?You’re luckier than you think

I once had such a bad streak of luck in a Scopa app that I set out to prove I was unlucky, so I started keeping track of my win-loss ratio. It didn’t surprise me that I lost the first two games, but then I won the next three. Then I lost two more, then won two more. When all was said and done, I ended up at more or less 50%, which is actually quite good, as I explain elsewhere. Why did I think I was so unlucky? I’ve read about this psychological phenomenon before; rather than appreciating our fortune, we humans have a habit of begrudging our misfortunes. This is probably related to not taking yourself too seriously.The bad

Not everyone gets a “fair” deal

Some people say that there’s no such thing as a “lucky streak”. To borrow a highly technical term from statistics, these people are what we call “morons”. As I wrote above, you can’t choose the cards you’re dealt; you can only choose how to play them. The second sentence matters a big deal, but you know what else matters? The first one. And, boy, do I get a lot of stinkers when playing. Imagine starting off with a table showing two sevens, a six, and an five, three of them golden; in your hand are a two, a three, and a four; and your opponent has a seven, a jack, and a six. If you play your cards just “right”, you’ll finish that hand losing by 2-0. What’s more, you’ve had these sorts of openings hands several rounds in a row. Don’t quote me the Central Limit Theorem or some other statistical law and pretend that lucky streaks don’t exist. Do you know the definition of “random”? Sure, I’ll get one hundred great hands in a row if I wait long enough, but that’s small consolation when I’m losing now, time after time after time. Maybe I don’t have one hundred years to wait for that string of one hundred great hands which will make up for my bad ones. And of course that begs the question as to whether I’m blessed with enough sense to use the cards I’m dealt as well as my opponents. On the other hand, if you start tracking your games, because you may discover that your streak of apparently bad luck is actually a streak of pretty good luck — you just didn’t value your success because you want more. Don’t be greedy; appreciate what you have!Partnering with an idiot will make your life worse

You can play on a team of one, but playing on a team of two can be much more fun, especially in Briscola. The strategy changes, and there are more surprises (in my opinion). Surprises are always fun. Well, almost always. It isn’t fun when you’re saddled with a moron, in particular with a moron who doesn’t understand basic strategy.Tough-talkers are often big losers

An ironclad law is that when an opponent’s messages mainly consist of hurling insults and boasting of his prowess (not necessarily at cards), and/or my lack thereof, I win. I once played a woman who, after winning the first round 4-0, announced that she would beat me handily, “perché io studio [le carte] e tu no” (“because I study [the cards] and you don’t”). I think she meant that she was counting cards, and she was right: I never trained myself to do that, and she may well have won that round for that reason. It’s a good strategy. Nevertheless, I proceeded to win the next 3 or 4 hands quite handily, and thus the game. She left the table without saying a word. I may well have won for no better reason than that she provoked me into paying attention. Had she exercised a little more humility, she may well have won the game. Another incident I enjoyed was when one man started the game by typing into the chat various insults unfit to reproduce here. I had to ask him what some of them meant, since my familiarity with Italian insults is not as strong as it should be. (Thanks, ma!) I otherwise ignored him and won. He left the table with additional insults, but even if I had lost, what would be the point of getting worked up about it? Imagine having to live with the sort of person who can express himself only with insults. Better yet — or worse yet, depending on your point of view — imagine having to live with yourself when you’re the sort of person who can express yourself only with insults. I’d rather be able to lose a game gracefully.The ugly

Feedback loops

A fun aspect of Scopa is a sequence of events like this:- Player A leaves a 4, a 3, and a 6 on the table.

- Player B has a 7, knows a 7 is usually a good card, so Player B takes 3 + 4 = 7.

- Player A has a 6, and sweeps. One guaranteed point.

- Player B curses his luck, and plays a 3.

- Player A has a 3, and sweeps again. Two guaranteed points.

Some people are out to trick you

Take me, for instance. When playing Scopa, I often set up a scenario exactly like the one described in “Feedback loops”. You’d best think real hard before giving someone an opportunity to take advantage of you. You don’t want to choose that, then be stuck with suffering it over and over again with no choice at all!A thing’s value can seem arbitrary

Why is primiera based on sevens? Why is the gold seven a point by itself? Why is l’asso the strongest card in Briscola, with three the second-strongest card? Besides, Scopa has these variants (and possibly others):- asso piglia tutto, where playing an ace sweeps all cards off the table, though it doesn’t earn a point;

- re bello, where the gold ten, like settebello (gold seven), is worth a point;

- Napula, where taking the golden 1, 2, and 3 means you get a point for every gold card taken in that sequence (that is, taking the golden 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 earns 4 points for taking 1-4).